Indigenous peoples’ rights

“How can responsible companies pursue profitable activities that have an inherently significant physical, social or cultural impact, ensure that their operations are not undermining the rights of indigenous peoples particularly when working in geographical areas that may have land right conflicts or complex histories or that are in or contiguous to protected areas or their margins?”

Dilemmas and case studies

- Access to water

- Child labour

- Community relocation

- Conflict minerals

- Corruption

- Cumulative impacts

- Doing business in conflict-affected countries

- Forced labour

- Freedom of association

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of speech

- Gender equality

- Health and safety

- HIV/AIDS

- Housing

- Human trafficking

- Indigenous peoples’ rights

- Living wage

- Migrant workers

- Non-discrimination and minorities

- Privacy

- Product misuse

- Security forces

- Stabilisation clauses

- Working hours

- Working with SOEs

This page presents an introduction to and analysis of the dilemma. It does so through the integration of real-world scenarios and case studies, examination of emerging economy contexts and exploration of the specific business risks posed by the dilemma. It also suggests a range of actions that responsible companies can take in order to manage and mitigate those risks.

What is the dilemma?

"How can responsible companies pursue profitable activities that have an inherently significant physical, social or cultural impact, ensure that their operations are not undermining the rights of indigenous peoples particularly when working in geographical areas that may have land right conflicts or complex histories or that are in or contiguous to protected areas or their margins?"

In many instances indigenous peoples will not have benefited fully from socio-economic development and their rights may not be sufficiently protected in law. This means they can be more susceptible to the economic and social impacts of business activity. In addition, it can be challenging for companies to identify (and by extension respect) those specific indigenous rights and interests that can sit outside mainstream norms. It is therefore important to consider factors that are specific to indigenous peoples when participating in local consultation and engagement processes by – whilst also applying the standard of ‘free, prior and informed consent' (FPIC) (see below).

Certain sectors – such as mining, oil and gas, infrastructure development, agro-commodities production, tourism, logging and pharmaceuticals – can, by their nature, have a particularly significant impact on the way of life of indigenous peoples. For example, mineral, hydrocarbon and other resources may be located in areas where the rights of indigenous peoples have not been properly documented. As an example, impacted land may have particular cultural and/or religious value to the indigenous community, which is not formally recorded. This can create a risk that is undermined by companies carrying out high-impact extraction activities.

Companies should seek to minimise such impacts to the best of their ability. This will require a thorough understanding of indigenous culture, religion, norms and values, which company employees may often find alien, obscure or difficult to understand. Yet they are vital to recognise and understand, so that negative impacts can be avoided, mitigated and monitored responsibly.

Moreover, businesses should be cognisant of the need to respect the rights of indigenous peoples as articulated by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the ILO Convention 169 on Tribal and Indigenous Peoples.1 These instruments underscore the requirement for the meaningful consultation of indigenous communities - with the objective of achieving their free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) - when business activities affect their lands.

Defining indigenous peoples

There has been no singular definition of indigenous peoples adopted at the international level. Rather, self-identification has been deemed to be the key criterion. The prevailing view among various stakeholders working on indigenous issues is that a specific definition is not necessary to safeguard the recognition and protection of their rights.

The ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Persons uses the following language in describing the peoples it aims to protect:

"Peoples in independent countries who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonisation or the establishment of present state boundaries and who, irrespective of their legal status, retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions".2

A somewhat different approach was adopted by the African Commission on Human and People's Rights (ACHPR) in its 2007 advisory opinion on the UNDRIP. The ACHPR emphasized as constitutive characteristics of indigenous peoples, a special attachment to and use of traditional lands and a state of subjugation, marginalisation, dispossession, exclusion and discrimination due to their different culture, way of life and livelihoods. This opinion assigned comparatively less weight to the association of indigeneity with descent from the ‘first inhabitants', because as the ACHPR stated, on these grounds and in the African context, the majority of Africans consider themselves indigenous.3

Many countries have not extended formal legal recognition to indigenous groups, which can put them at risk of discrimination and without access to remedy for the violations they might encounter as a consequence. A country's approach to formal recognition of indigenous groups is often conditioned by political, cultural, social and economic considerations, such as concerns that FPIC rights will impede commercial investments, or in some cases, that recognition may result in disruption to territorial integrity. For instance, in many African countries, tribal people make up the majority of the population and ruling elites may be concerned that if different indigenous groups were to receive recognition, the result could be a further fracturing of states that are already lacking cohesion.

The UN estimates that some 370 million indigenous peoples live in more than 90 countries around the world.4 There are indigenous peoples on every continent, representing thousands of cultures, languages and unique backgrounds. International organisations, including the UN, acknowledge that there are currently approximately 30 ‘uncontacted' peoples in countries such as Brazil, Peru and Papua New Guinea, known only through anthropological evidence.5

In countries such as Bolivia and Guatemala, indigenous peoples represent the majority of people, while in others they represent very small minorities. Some states contain hundreds of distinct peoples and language groups, while others contain only a few major groupings. In many locations indigenous groups represent the fastest-growing portions of local populations, based on birth rate trends.6

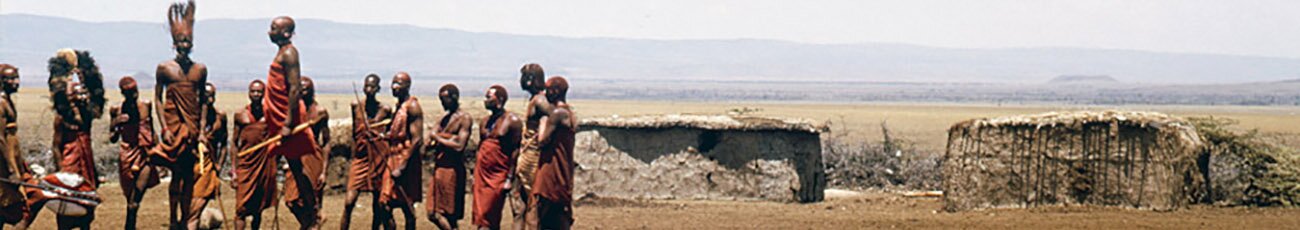

While indigenous communities reside in a variety of locations, including in urban and semi-rural areas, many groups inhabit rural and remote areas, which set them apart from the rest of the population. In this latter context, these groups are often dependent on subsistence-based activities such as hunting, fishing, gathering and small-scale herding and farming. In many cases they rely on traditional medicine to maintain health.

This dilemma will deal only with indigenous peoples' rights, as other distinct groups – such as religious and ethnic minorities – are addressed at length through separate dilemmas.

Issues of concern

Based on historical political relationships as well as contemporary economic dynamics, indigenous peoples generally represent the most marginalised populations around the world.7 According to the 2015 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, Victoria TauliCorpuz, indigenous peoples account for 5% of the world's population, but 15% of those living in poverty. The report also notes that 33% of all people in extreme rural poverty are from indigenous communities.8

The following are recurring areas of concern that are raised by different stakeholders involved in the protection and promotion of indigenous peoples:

- Barriers to participation in formal decision-making structures at the national level (including, for example, through the denial of citizenship)

- Lack of – or diminished access to – justice to address the infringement of their rights

- Lack of legal recognition of land ownership, resulting in dispossession of land and displacement

- Lack of recognition or integration of customary decision-making structures by the state

- Discrimination and prejudice within broader society

- Inadequate consultation related to development projects that directly impact on indigenous livelihoods9

Such issues often relate to factors such as physical remoteness, racial and cultural prejudice, a historical lack of respect for indigenous institutions, values and forms of ownership, the political, educational and economic vulnerability of some indigenous groups (allowing for a degree of impunity on the part of abusers). In extreme cases, these can contribute to very serious abuses. For example, according to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues' 2010 publication on the ‘State of the World's Indigenous Peoples', "forced removal, clear-cutting of forests, military abuses, and deaths and disappearances are taking place in India, the Philippines, Panama, the United States, Canada, Malaysia, Costa Rica and Chile".10

Real-world examples

There are myriad examples of the ways in which businesses may encounter indigenous rights issues within their operations. This is further complicated by the fact that different indigenous groups take vastly disparate approaches to their relationships with business and national governments.

While some groups prefer isolation and immunity from forces that would act to undermine their traditional way of life, others seek vigorous engagement with business groups to seize the opportunity to prosper from their presence. Sometimes those seeking benefit are not representative of the overall indigenous communities they purport to speak for. For example, women are sometimes disadvantaged relative to ruling (often male) traditional leaders, or they are not included in consultation processes. As a result, it is important that businesses understand the specifics of their local operating environment to appreciate such risks and formulate proper, broad-based consultation and mitigation techniques.

Development projects in the extractives sector threaten indigenous land titles in Honduras

In November 2015, the Special Rapporteur on the human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, expressed concern regarding the "critical situation" faced by indigenous peoples in Honduras. Specifically, she expressed concern about the "the lack of full recognition, protection and enjoyment of their rights to ancestral lands, territories and natural resources" as well as impunity for violent attacks on indigenous communities. The Rapporteur called on the Honduran government to implement the full agreement reached with the community to investigate and sanction those responsible for land sales and environmental destruction, to finalize the ‘saneamiento' process – the titling of collective lands - and to return third parties on indigenous lands to their places of origin.

Special Rapporteur raises concerns over impunity for violations of the rights of indigenous people in Paraguay

In August 2015, the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, expressed concern regarding the continued violation of the rights of indigenous groups in Paraguay, particularly in relation to security of lands, territories and resources. Although article 64 of the Paraguayan constitution recognises the right of indigenous communities to communal ownership of their lands, a number of legal and administrative barriers prevent groups from exercising this right. According to the 2012 census, 375 indigenous communities had put forward land claims, while another 134 stated that they are landless. In addition, 145 communities reported that they are experiencing violations of their land rights, including the wrongful appropriation of land by public agencies and business enterprises, the occupation of land by small-scale farmers and the existence of overlapping land titles and the rental or loan of land to third parties. The Special Rapporteur also noted the widespread problem of non-compliance with the State's obligation to engage in consultation before the adoption of legislative, political or administrative measures that directly affect indigenous communities and their land. Similarly, the lack of redress for cases of human rights violations remains a significant concern.11

Human Rights Watch says indigenous women and girls are overrepresented among homicide victims in Canada

In its 2015 World Report, Human Rights Watch released data from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) which found that the rates of violence against indigenous women and girls are double previous estimates. Of the total 1,818 cases of murders and disappearances between 1980 and 2012, indigenous women and girls constitute 16 per cent of female homicide victims, despite making up only 4.3 per cent of Canada's female population. Human Rights Watch has documented the RCMP's failure to protect indigenous women and girls from violence, including abusive police behaviour, excessive use of force and sexual assault. At the time of the publication of the Human Rights Watch report, the Canadian government had failed to recommend an independent inquiry or steps to address police accountability for misconduct.12

Barro Blanco Hydroelectric Dam suspended over non-compliance with Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Panama

In February 2015, Panama's National Environmental Authority (ANAM) temporarily suspended the construction of the Barro Blanco dam due to non-compliance with its Environmental Impact Assessment requirements. The dam was previously approved by the UN Clean Development Mechanism despite risks of flooding in the territory of the indigenous Ngäbe communities. The landmark ruling to suspend the dam construction was triggered by an administrative investigation of non-compliance in the environmental impact assessment, including agreements with the affected communities. The National Environmental Authority found not only deficiencies in consultation with communities ahead of project initiation, but also repeated failures to manage sedimentation and erosion, poor management of solid and hazardous waste and the absence of an archaeological management plan to protect petroglyphs and other archaeological findings.13 Peruvian government disregards human rights obligations to approve expansion of Camisea project.

In January 2014, the Peruvian government approved expansion plans for the Camisea gas project. Camisea – reported to be Peru's largest gas project – is located in the Kugapakori-Nahua-Nanti Reserve. The government's decision to approve expansion plans disregards the recommendations of the UN Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD). In March 2013, CERD sent a request to Peru's ambassador to the UN urging the government to "suspend immediately" plans for the expansion of the Camisea gas project. The letter noted that the project "could threaten the physical and cultural survival of the indigenous peoples living there and impedes their enjoyment of their economic, social and cultural rights." 14

- For examples of how companies such as De Beers and Gold Fields are respecting the rights of indigenous people through community engagement, promoting socioeconomic development and local employment, see:

- Indigenous Peoples' Rights case studies

- Please contribute your commentary or suggestions to our online discussion forum:

- Indigenous peoples' rights online discussion forum

1 ILO, 1989, Convention 169 on Tribal and Indigenous Peoples, http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C169. The ILO's activities in the area of indigenous and tribal peoples falls within two main areas of activity: the promotion and supervision of the two Conventions relating to indigenous and tribal peoples; and technical assistance programmes to improve indigenous and tribal peoples' social and economic conditions. The other relevant convention is ILO Convention 107 on Indigenous and Tribal Populations (1957).

2 ILO, 1989, Convention 169 on Tribal and Indigenous Peoples, http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C169. The ILO's activities in the area of indigenous and tribal peoples falls within two main areas of activity: the promotion and supervision of the two Conventions relating to indigenous and tribal peoples; and technical assistance programmes to improve indigenous and tribal peoples' social and economic conditions. The other relevant convention is ILO Convention 107 on Indigenous and Tribal Populations (1957).

3 ACHPR, 2007, Advisory Opinion of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Available at http://www.achpr.org/files/special-mechanisms/indigenous-populations/un_advisory_opinion_idp_eng.pdf.

4 UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), 2010, State of the World's Indigenous Peoples', 2015 http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/2015/sowip2volume-ac.pdf .

5 See Survival International, 2011, Uncontacted Tribes, http://www.uncontactedtribes.org.

6 C. Leuprecht, The Demographic Security Dilemma, Yale Journal of International Affairs, 5(2), Spring/Summer 2010, http://yalejournal.org/2010/07/the-demographic-security-dilemma-2/.

7 UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2010, State of the World's Indigenous Peoples, http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/SOWIP_chapter6.pdf.

8 United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2015, Report of the Special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples. Available at http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G15/173/83/PDF/G1517383.pdf?OpenElement.

9 The 2003 Extractive Industries Review undertaken by the World Bank suggests that large scale infrastructure projects have resulted in increased impoverishment and cultural disintegration. See: The World Bank Group and Extractive Industries, 2003, The Final Report of the Extractive Industries Review, Vol. 1.

10 UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, 2010, State of the World's Indigenous Peoples, http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/SOWIP_chapter6.pdf.

11 OHCHR, 2015, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, August 2015, ‘The situation of indigenous peoples in Paraguay,' Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/IPeoples/SRIndigenousPeoples/Pages/SRIPeoplesIndex.aspx

12 Human Rights Watch, 2015, Word Report, Available at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/wr2015_web.pdf

13 Carbon Market Watch, 2015, ‘UN registered Barro Blanco Hydroelectric Dam temporarily suspended over non-compliance with Environmental Impact Assessment,' Available at: http://carbonmarketwatch.org/un-registered-barro-blanco-hydroelectric-dam-temporarily-suspended-over-non-compliance-with-environmental-impact-assessment/

14 Forest Peoples Programme, 2014, ‘Camisea project expansion plans given green light by Peruvian government,' Available at: http://www.forestpeoples.org/topics/extractive-industries/news/2014/01/camisea-project-expansion-plans-given-green-light-peruvian

Common dilemma scenarios

There are several common themes or issues relating to indigenous peoples, regardless of geographic location:

Historical lack of trust with respect to state authorities

In many different settings indigenous groups have experienced varying degrees of social marginalisation or even outright persecution at the hands of the government or groups within society that have been able to act with impunity. This has often been driven by economic interests, creating further distrust of business, on whose behalf governments are often seen to be working. This history of negative treatment may have long-term consequences, for example in relation to permanent environmental degradation and pollution, the resettlement of indigenous communities away from their traditional homelands, or an influx of non-indigenous people that changes the cultural character of a place. Historical treatment has been so severe that in some cases – such as in Canada15 and Australia16 – the government has been compelled to issue a formal apology to the community and compensate victims for their complicity in human rights violations. A related lack of trust can be exacerbated by insufficient access to remediation mechanisms (such as judicial remedies and/or company complaints procedures).

As a result, in some settings, indigenous groups are hesitant to engage with different stakeholders when responding to project proposals or government statements promising improved practices and better regulations – or are even actively hostile to the same.

Government policy fails to protect indigenous rights

Indigenous rights that are recognised by national governments vary. Typically they relate to self-government, land ownership (either individual or collective), land access, environmental conservation, resource rights and the protection of cultural heritage. General rights related to non-discrimination are also of relevance in this context.

According to the Secretariat of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples, however, "many indigenous communities are adversely affected by policies, projects and programs, since their distinct visions of development, their concerns and way of life are all too often ignored by national or local level policy makers or administrators".17

Examples include Moroccan law, which prevents the inclusion of children with Amazigh (Berber) names in the civil registry of births because of the manner in which a "Moroccan name" is conceived. Likewise, Nepalese law prohibits any indigenous person from holding office in the judiciary. In Cameroon, many Batwa have difficulty obtaining citizenship identification papers.

It can be challenging for indigenous groups to seek fruitful engagement or assistance at the international level in order to address ill treatment at the hands of the state.

For example, according to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples, the UN system does not provide specific juridical mechanisms for the resolution of conflicts to which indigenous peoples are a party or which result in the violation of the rights of group members.18 For instance, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) does not provide legal standing to indigenous individuals or collectives to pursue litigation against states or third parties such as multi-national corporations.19 Furthermore, states need to endorse complaint mechanisms and/or optional protocols associated with regional courts and UN treaty bodies before the grievance mechanisms can be activated.

Although national policy is not always prejudicial to the rights of indigenous peoples, the following may well be of concern for indigenous peoples engaging with the state:

- Political agendas that view indigenous peoples as an obstacle to national development

- Economic mechanisms that transfer benefits from resource extraction to national or provincial centres instead of local areas

- A lack of coordination among different branches of government on issues of concern to indigenous groups resulting in convoluted or conflicting policies

- Implementation shortcomings of existing laws that promote the rights of marginal groups, including indigenous peoples

Land rights are fragile, poorly documented and/or ambiguous

The land indigenous peoples have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used is generally of great significance; it can often be seen as a physical representation of their culture, spirituality and identity. Spiritual attachment and a sense of collective belonging to land, including in relation to burial rituals, is an especially salient issue for indigenous peoples.20 Moreover, and on a more pragmatic level, such land often represents a vital source of food, medicine, clothing and shelter, and provides the basis for self-government and economic viability.

Commercial activities ranging from natural resource extraction, ranching, infrastructure projects, tourism and bio-prospecting can seriously undermine such interests. This dynamic can be exacerbated by unclear arrangements around, and recognition of, property rights – a vital issue for businesses to consider and manage prior to investment.

The international human rights law standard for indigenous ancestral land requires states to give legal recognition and protection to the right to lands and territories which indigenous peoples have traditionally owned or occupied.21 The Inter-American court judgments elucidate these standards in Awas Tigini v. Nicaragua and Saramaka v. Suriname.

Land and resource rights may be formally recognised by treaty or land claim settlements with the national government, or they may be enshrined in national legal frameworks through recognition of customary law at the local level. Specific laws that identify indigenous groups for special treatment are relatively rare – Australia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, Guyana, India, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Russia, Taiwan, Thailand and the United States fall into this category, but the majority of countries do not have specific legal arrangements in this respect.

In countries where land rights are governed by customary law, such as Papua New Guinea, negotiations may have to take place with each traditional owner involved. This may include an individual, a family clan or a more complex set of actors. In addition to the multiplicity of stakeholders involved in such processes, ownership can overlap and relate to different categories of land use. In countries such as Peru or Venezuela, which have sought to formalise land ownership through the issuing of titles, the boundaries may be more discrete, but the customary use of the land and rights to any shared resources may still introduce a significant degree of complexity to related transactions.

In Canada, Australia, the Philippines, New Zealand and (on a smaller scale) the US, there are hundreds of active claims and treaty processes in the courts as a result of judicial decisions or new legislation. As a result, formal titling in some areas remains contentious and litigation can extend for years – a process which is expensive and time consuming for all parties with equity at stake.

Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC)

The concept of Free, Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) relates to land use and physical and intellectual property rights.22 The duty to consult is affirmed as an overarching principle in Art. 19 of UNDRIP and also referred to in ILO No. 169. General Recommendation No. 23 (1997) promulgated by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) requires states to "Ensure that members of indigenous peoples have equal rights in respect of effective participation in public life and that no decisions directly relating to their rights and interests are taken without their informed consent".23

FPIC encompasses varying requirements and methodologies that are applicable to policies, programmes, projects, and administrative and legislative measures impacting indigenous rights in an increasing number of national, international and regional venues.

The International Labour Organization's Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169 refers to the principle of free and informed consent in the context of relocation of indigenous peoples from their land (Art. 16). In addition, the Convention requires that States fully consult with indigenous peoples and ensure their informed participation, as it relates to development projects, national institutions and programmes, land and resources.24 Similarly, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) has promulgated General Comment 23 that calls upon States to "ensure that members of indigenous peoples have rights in respect of effective participation in public life and that no decisions directly relating to their rights and interests are taken without their informed consent".25

At the regional level, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights interprets human rights law to include the taking of "special measures to ensure recognition of the particular and collective interest that indigenous people have in the occupation and use of their traditional lands and resources and their right not to be deprived of this interest except with fully informed consent, under conditions of equality, and with fair compensation".26

In Europe, the European Union Council of Ministers' 1998 Resolution entitled, ‘Indigenous Peoples within the framework of the development cooperation of the Community and Member States' provides that "indigenous peoples have the right to choose their own development paths, which includes the right to object to projects, in particular in their traditional areas."27

The need to seek FPIC is attached to a wide variety of bodies and sectors "ranging from the safeguard policies of the multilateral development banks and international financial institutions; practices of extractive industries; water and energy development; natural resources management; access to genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge and benefit-sharing arrangements; scientific and medical research; and indigenous cultural heritage".28

International financing organisations have also integrated the concept into their lending conditions. For example, the International Finance Corporation has integrated the requirement for FPIC from indigenous peoples in its latest 2012 Performance Standards. In particular, Performance Standard 7: Indigenous Peoples requires FPIC if a project:

Impacts on land and natural resources subject to traditional ownership or customary use

Requires the relocation of indigenous peoples from lands/away from natural resources subject to traditional ownership or customary use

Impacts on "critical cultural heritage"29

Likewise, the World Bank's Operational Manual 4.10 (2005) requires indigenous peoples' broad community support is obtained through culturally appropriate and collective decision-making processes after meaningful and good faith consultation, as well as informed participation at each stage and throughout the life of the project. Similarly, the Inter-American Developmental Bank (IDB) Strategies and Procedures on Socio-Cultural Issues as Related to the Environment mandate that the IDB will not support projects affecting tribal lands and territories "unless the tribal society is in agreement."30

Thus, although FPIC generally represents a ‘soft law' obligation (with notable national exceptions), it has been gaining normative strength at the regional and international level, meaning that the implementation will be less discretionary over time. Furthermore, it has become a ‘hard obligation' for those companies seeking financing from the IFC – or to meet the IFC Performance Standards as a means to providing assurance to other financing organisations (a common practice when operating in more challenging environments).

Disparate local community stakeholders with conflicting priorities

In many cases, ‘local communities' will be composed of both indigenous and non-indigenous peoples, and more than one group of indigenous people. As a result, navigating the respective obligations, responsibilities and requirements of these disparate groups requires careful management. This is particularly the case if companies are to avoid a) antagonising portions of the population who feel they are not being offered the same level of protection/benefit as other groups; and b) creating new conflicts or stoking existing tensions between competing groups.

For example, indigenous peoples may focus their efforts on protecting group-specific ‘ancestral' interests. As a result, they are likely to be less amenable to certain project-related activities than non-indigenous groups. This might include, for example, the construction of project-related infrastructure on culturally-significant land – infrastructure that may be vital for a project to proceed. This may conflict with the interests of non-indigenous groups for whom the land holds no spiritual or symbolic value – but who are keen for a project to proceed due to the economic opportunities it will create.

Likewise, indigenous groups will be more likely to place emphasis on retaining and strengthening customary collective structures, including landownership and decision making – and ensuring they play a key role in decision-making with respect to a project. Given such structures are likely to exclude non-indigenous people – and to exercise power outside of the state framework (which will often be of a democratic nature) – the potential for tensions and conflict is obvious.

Resettlement issues

Various studies have shown that community relocation can – where it is not managed responsibly – have serious and long-term consequences for those affected. Community relocation is often required in relation to extractive projects – due to the fact that high-impact extraction activities such as drilling and mining must necessarily take place wherever the hydrocarbon and mineral deposits are located. According to a study undertaken by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), for example, re-settlement is often associated with:

- Permanent dispossession of ancestral lands and loss of land rights

- Loss of cultural integrity and the breakdown of family and governance structures

- Loss of spiritual and knowledge systems

- Loss of identity and collective cohesion

Such issues have prompted most international institutions to develop strong guidelines regarding resettlement activity. Indeed, the ICMM has itself made it clear that "companies should make every effort to avoid resettlement of indigenous communities" in its 2015 Good Practice Guide on Indigenous Peoples and Mining.[31] Likewise, institutions such as development banks have intensified efforts to integrate and coordinate policies regarding indigenous peoples with guidelines on resettlement.32

Capacity constraints amongst indigenous groups and within business

Different indigenous groups have varying degrees of experience and different levels of capability when it comes to engaging with businesses and government agencies. Furthermore, there are a wide range of indigenous governance structures in place, of varying effectiveness and representative legitimacy. This can make it difficult for indigenous groups to properly represent and promote their interests when engaging with companies and officials. It can also make it more challenging for responsible companies and officials to engage meaningfully with such groups – including the identification of relevant community concerns – and thus to establish sustainable, constructive relationships that can be relied upon in the future.

Likewise, the establishment and maintenance of such relationships can require highly specialist skills and ways of thinking that are not always common within many companies. These include:

- Cross-cultural communication

- Land use planning and resource management expertise

- Cultural assessment skills

- Knowledge of indigenous rights

- Conflict resolution expertise

- Community capacity building/economic development capabilities

As a result, capacity-building, both within local communities and within companies themselves, is likely to be an essential component of responsible management when operating in indigenous areas.

15 On 11 June 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper made the apology to the indigenous peoples of Canada for forcing aboriginal children to attend state-funded Christian boarding schools aimed at assimilating them.

16 In February 2008, former Prime Minister Rudd apologised for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country.

17 Division for Social Policy and Development/UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2005, Background Paper prepared by the Secretariat of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/engagement_background_en.pdf.

18 Ibid., at Chapter 7.

19 Ibid.

20For example, in the Maya (Sumo) v. Belize case adjudicated before the Inter-American Court on Human Rights, the petitioners clearly attached importance to remote forested lands that they regarded to be sacred and are used for ceremonial purposes as well as burial grounds. See: Maya indigenous community of the Toledo District v. Belize, Case 12.053, 2005, Report No. 40/04, Inter-Am. C.H.R., OEA/Ser.L/V/II.122 Doc. 5 rev. 1, http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/cases/40-04.html..

21 See Art. 26 of UNDRIP and Art. 14 of ILO Convention No.169. The latter also covers lands which indigenous peoples have traditionally had access to for their subsistence and traditional activities.

22 For an extensive explanation of FPIC, see the OHCHR's 2005 Legal Commentary on the Concept of Free, Prior and Informed Consent, www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/indigenous/docs/wgip23/WP1.doc

23 See General Recommendation 23 concerning Indigenous Peoples, adopted at the Committee's 1235th meeting, 18 August 1997. UN Doc. CERD/C/51/Misc.13/Rev.4 at para 4(d).

24As of July 2013, the following states have ratified ILO Convention 169: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Dominica, Ecuador, Fiji, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nepal, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, Spain and Venezuela. See: http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/ratifce.pl?C169

25 See: UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 1997, General Comment 23, http://sim.law.uu.nl/SIM/CaseLaw/Gen_Com.nsf/a1053168b922584cc12568870055fbbc/e399bf13d06afbc4c12568870052ea1c?OpenDocument.

26 Mary and Carrie Dann v. United States, Case 11.140, 2002, Report No. 75/02, Inter-Am. C.H.R.

27 European Union Council of Ministers, 1998, Resolution on Indigenous Peoples within the Framework of the Development Cooperation of the Community and Members States, http://eeas.europa.eu/human_rights/ip/docs/council_resolution1998_en.pdf.

28 Ibid.

29 IFC, January 2012, Performance Standard 7: Indigenous Peoples, http://www1.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/1ee7038049a79139b845faa8c6a8312a/PS7_English_2012.pdf?MOD=AJPERES [Accessed on 2 August 2013].

30 IDB, 1990, Strategies and Procedures on Sociocultural Issues as Related to the Environment, http://idbdocs.iadb.org/wsdocs/getdocument.aspx?docnum=362137 [Accessed on 2 August 2013].

31 ICMM, 2015, Good Practice Guide to Indigenous Peoples and Mining, http://www.icmm.com/document/9520 [Accessed on 23 November 2015].

Examples

Business dilemmas involving indigenous issues can be found in the majority of BRICs and N-11 emerging economies.33 Research indicates that there are similarities among the types of rights violations that occur in these countries and they are often related to: land issues, political disenfranchisement, economic discrimination and poor development indicators when compared to general population.

Examples of scenarios companies might face when operating in emerging economies include:

Botswana: In February 2015, Bushmen in the Kalahari reported that they are unable to engage in subsistence hunting because this results in their arrest on the grounds of committing "wildlife crime." The comments on the Bushmen's struggle for recognition of hunter-gather rights followed a debate on this issue at a symposium hosted by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).34 On 3 March 2011, the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples expressed grave concern over the treatment of Bushmen and Bakgalagadi tribes in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve at the hands of the government. The tribes are allegedly pressured into leaving the area through the denial of essential services, including water, from the area despite the fact that a 2006 High Court ruling legitimised their land claims. This treatment is particularly controversial given that the government has consented to both diamond exploration and eco-tourism elsewhere in the Game Reserve.35

Brazil: The National Indigenous Foundation (FUNAI) estimates that there are 460,000 indigenous people living on indigenous lands in Brazil, and an additional 100,000 to 190,000 in other areas, including urban areas. Some indigenous settlements in the rainforest contain groups that still live in voluntary isolation. Although Brazil has constitutional and other legal protections for indigenous peoples, plans to develop and industrialise the Amazon threaten indigenous land rights and development. Many of the surviving indigenous groups in Brazil no longer live on their traditional lands, which has resulted in an erosion of their cultures, traditions and languages. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 15.5% of the Brazilian population lives in extreme poverty, but the rate for indigenous people is 38%. Extreme poverty and a range of related social ills notably afflict the Guarani, Kaiowá and Nhandeva peoples of Mato Grosso do Sul. The state has the highest rate of childhood mortality due to precarious health conditions and inadequate access to water and food.

In August 2015, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples urged the Brazilian government to "ensure that the human rights of the Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous peoples are fully respected, in strict compliance with international standards."36 She noted that 6,000 members of the community, living in the State of Mato Grosso do Sul, were resisting forcible eviction by law enforcement authorities. The Rapporteur also expressed grave concern over the use of militias which are deployed to attack and intimidate communities, sparking conflict that has resulted in the death of nearly 300 Guarani and Kaiowá individuals since 2003.

Indonesia: In June 2015, the Alliance of Indigenous People (AMAN) called on President Widodo to follow through on his election pledge to establish a taskforce on indigenous people.37 AMAN, which represents a network of approximately 2,253 indigenous groups, expects the taskforce to: accelerate the adoption of a law recognising and protecting indigenous peoples' rights; establish a National Commission for Indigenous People; and facilitate access to remedy for indigenous people criminalised for using ancestral lands.

Indigenous people supported President Widodo in the presidential election campaign of 2014, largely in the expectation that his administration would provide redress for past violations of indigenous land rights. In particular, AMAN is seeking that Widido implement the Constitutional Court ruling of May 2013 which confirmed that "customary forests" could not be categorised as "state-owned forest" lands. This interpretation of the 1999 forestry law protects customary forests from being included as state-forest concessions and, according to AMAN, it could impact on 30% of Indonesia's forests. The government has yet to adopt the corresponding legislation required for implementation.

Colombia: On 6 February 2015, the Association of Traditional Indigenous Authorities of the Wayuu Shipia Wayuu (ATIAWSW), petitioned the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights. The Association asked the Commission to issue emergency cautionary measures to the Colombian government to allow the Wayuu community to regain access to the Rancheria River which was previously dammed by the government. The communities allege that open-cast coal mining at the Cerrejon mine, in La Guajira state, North-Eastern Colombia has adversely affected their current water supply.

BHP Billiton, Anglo American and Xstrata co-own the opencast Cerrejon coal mine situated in La Guajira state, North-eastern Colombia. The mine has attracted controversy because the Wayuu indigenous community is reported to have suffered a series of alleged human rights violations as a result of its operations. In 2001, for example, before the mine was purchased by these companies, residents of the Tabaco villages were reported to have been forcibly evicted.

Allegations of forced evictions continue. In the summer of 2013, eight families in the farming community of Roche were told that they would be evicted by force if they did not come to an agreement with Cerrejón regarding a relocation deal. Following planned protests in London and Boston, the eviction was called off and a deal was signed. However, the families were provided with only one hectare of land each; a violation of the Colombian government's ‘Unidad Familial Agricola' which specifies a minimum quantity of 72 to 98 hectares of land to support a farming family.38

India: The government has taken steps to amend legislation on the protection of indigenous peoples. The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act 2006 is a key piece of legislation that stipulates the rights of forest dwellers and others who depend on forests for their livelihoods and cultural identity. The 2006 Act is supported by many judicial decisions that demonstrate a willingness to proactively ensure indigenous rights are safeguarded.

The government's overall record in this area remains mixed. Indian law automatically classifies all underground minerals as state property and does not require groups seeking to exploit such resources to obtain consent from affected communities. However, in the case of the Vedanta bauxite mine in the Niyamgiri hills of Orissa, the Indian courts have respected the right to consultation of the affected Dongria Kondh communities. In 2014, the Ministry for Environment and Forests rejected the proposal of Vedanta Resources to develop a bauxite mine in this area.

A 2011 report by the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact funded by the ILO has found that more than half of India's mineral wealth has been obtained through the violation of indigenous peoples' rights.39 Of particular concern is the high concentration of mineral deposits in areas inhabited by the Adivasi indigenous group, which lacks constitutional protection of their land and resources.40 The report also indicates that legislation allows the government to acquire lands upon payment of cash compensation for any public purpose, including mining.41

Mexico: In November 2015, Mexico's Supreme Court upheld the right of indigenous communities to consultation on development projects affecting their lands.42 The Court applied an injunction against Mexico's agriculture ministry, which had granted permission to use genetically modified seeds in the states of Yucatan and Campeche, allegedly without conducting meaningful consultation. Article 2 of Mexico's 2008 Constitution guarantees the right of indigenous peoples to self-determination and to consultation regarding development plans – although exceptions exist for "strategic" issues, such as hydrocarbons and petroleum. Mexico is also one of only 22 countries worldwide to have ratified the International Labour Organization Convention on Indigenous Peoples (No. 169).

In practice, however, projects often go ahead without the knowledge or consent of local communities. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) held a thematic hearing on 28 March 2011 on the topic of land tenure and the human rights situation of indigenous peoples. Petitioners participating in the hearing discussed the prevalence of ‘agrarian conflicts' whereby indigenous people defending their land faced harassment. The IACHR meeting also revealed that progress made toward re-distributing land to indigenous groups has receded considerably.

Levels of impoverishment among indigenous peoples continue to be extremely high. As a result, many indigenous groups feel compelled to sell their land, which can result in long-term destitution. Private ownership of ancestral land and the consequent dispossession are compounded by the fact that indigenous peoples are poorly represented in the bodies that address agrarian conflicts and have the power to make pivotal political decisions.

Nigeria: Nigeria is home to a significant number of ethnic sub-groups, many of which might be considered indigenous peoples. The Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People represents a community of approximately 850,000 residing in the oil and gas producing Niger Delta region.43 The Movement has documented an array of human rights violations against the population, the majority of which are associated with hydrocarbon development. These range from a lack of access to social services and political marginalisation – through to assassinations and violence perpetrated by the security forces.

In 2014, a London court ruled that Shell must pay £55m in compensation to Ogoni farmers and fishermen whose lives were devastated by two large oil spills in 2008 and 2009. Shell accepted responsibility for the operational spills, but argued that oil theft and illegal refining were the main cause of environmental damage. The company stated that communities will continue to be negatively impacted unless ‘real action' is taken against such activities.44

This was subsequent to an US$15.5 million an out of court settlement Shell made in relation to accusations that it was complicit in the deaths of nine activists belonging to the Movement in 1995, including Ken Saro-Wiwa. Despite the payment to the activists' families, Shell denies liability. The case was filed in the US under the Alien Tort Claims Act. In April 2013, the US Supreme stymied further efforts by activists in Nigeria to sue Shell in the US under the Alien Tort Claims Act in a precedent-setting decision that considerably restricted the ability of foreign plaintiffs to seek redress in the US courts for acts committed abroad.

In the early 1990s, Saro-Wiwa was a vocal critic of Shell, as well as its impact on local Ogoni communities and the environment. All nine activists were reportedly tortured by Nigerian security forces and were hanged for allegedly murdering political rivals in November 1995 following a trial that human rights activists denounced as a sham. The plaintiffs claimed Shell provided the military with transportation, including helicopters.

The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation has reported that the Nigerian Land Use Act effectively divests the Ogoni people of their rights of ownership and possession of land and its resources.45 In addition, the Petroleum Decree is reported to deny the right to consultation and participation in the exploitation of natural resources to the local Niger Delta population, placing this right only in the hands of foreign corporations in collaboration with the Nigerian federal government. Human Rights Watch has noted that the militarisation of the Niger Delta has increased the risk of abuses relating to the actions of the public security forces.46

Philippines: There are an estimated 12-15 million indigenous peoples in the Philippines who constitute 15% of the total population.47 They occupy more than 10 million hectares of the total landmass of 30 million hectares.

The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) requires the consultation of indigenous groups prior to any projects that might be implemented or have an adverse impact on their communities. However, according to the Indigenous Peoples Rights Monitor, other parallel legislation – including the 1995 Mining Act – potentially conflicts with the IPRA. In addition, the National Integrated Protected Area Systems (NIPAS) restricts the conduct of indigenous groups within their own lands if they overlap with areas designated as national parks.

Given the dispersed presence of indigenous groups throughout the country, they are exposed to a variety of economic activities including mining, dams and other energy projects, large agri-business operations and eco-tourism. The adverse impacts from these ventures are manifold: livelihoods are compromised, the environment is degraded and in some cases such activities have caused socio-political divisions and animosity between and within groups.

32 World Bank, 1991, Operational Directive 4.20 on Indigenous Peoples, http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/835cc50048855270ab94fb6a6515bb18/OD420_IndigenousPeoples.pdf?MOD=AJPERES [Accessed on 2 August 2013].

33 The BRICs countries are Brazil, Russia, India and China. The Next-11 countries are Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, South Korea, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Turkey and Vietnam.

34 Survival International, 28 February 2015, Legal analysis finds tribal peoples persecuted unjustly for ‘wildlife crime'. Available at http://www.survivalinternational.org/news/10675

35 Survival International, 2010, Wilderness Safaris, http://www.survivalinternational.org/about/wilderness-safaris [Accessed on 2 August 2013].

36 OHCHR, 2015, UN rights expert urges Brazil not to evict Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous peoples from their traditional lands. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=16308&LangID=E [Accessed on 23 November 2015].

37 Jakarta Post, 8 June 2015, AMAN reminds Jokowi about pledge to forest people. Available at http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/06/08/aman-reminds-jokowi-about-pledge-forest-people.html

38 London Mining Network, 2014, Cerrejón Coal, Colombia: ‘an abusive marriage, full of machismo,' Available at: http://londonminingnetwork.org/2014/06/cerrejon-coal-colombia-an-abusive-marriage-full-of-machismo/

39 Asian Indigenous Peoples Pact, 2011 Annual Report, http://www.forestpeoples.org/region/asia-pacific/news/2012/04/asian-indigenous-peoples-pact-aipp-2011-annual-report.

40 The high profile campaign and lawsuits involving Vedanta's proposed aluminium mining project in Orissa has put the vulnerable situation of the Adivasi into high relief. See, for example, http://www.survivalinternational.org/news/5546.

41 India Today, February 2011, India's mineral wealth obtained by violating tribal rights, says ILO study, http://indiatoday.intoday.in/site/Story/128945/india/a-report-by-international-labour-organisation-states-that-indias-mineral-wealth-is-obtained-by-violating-tribal-rights.html.

42 Telesurtv, 5 November 2015, Mexico court blocks Monsanto until indigenous groups consulted. Available at http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Mexico-Court-Blocks-Monsanto-Until-Indigenous-Groups-Consulted-20151105-0021.html.

43 Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO), 2011, Ogoni, http://www.unpo.org/members/7901

44 The Guardian, 2015, Shell announces £55m payout for Nigeria oil spills,' Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jan/07/shell-announces-55m-payout-for-nigeria-oil-spills

45 Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO), 2011, Balochistan People's Party, http://www.unpo.org/members/7901 .

46 Human Rights Watch, 2011, Nigeria Section, http://www.hrw.org/africa/nigeria .

Risks to business

International law

The right to be free from discrimination can found in several international human rights instruments as it is a part of the core prohibited aspects of discrimination. Several international human rights covenants outlaw discrimination based on race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Indigenous rights could fall under general anti-discrimination categories or be dealt with in specific laws that are tailored to their collective rights.

As with all human rights, it is incumbent on the state to promote and enforce the rights of indigenous peoples. Nonetheless, as is stipulated in the UN Special Representative on Business and Human Rights' Guiding Principles, companies have a duty to respect and support this right as applicable.

States that ratify international human rights treaties will have relevant national legislation in place implementing the terms of these legal instruments and allowing for adjudication at the national level. That said, this by no means ensures the provision of equal legal protection across all countries, not least because no international human rights treaties have achieved universal ratification.

The International Labour Organisation's Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169 stipulates that governments have the responsibility for "developing co-ordinated and systematic action to protect the rights of indigenous and tribal peoples (Article 3) and ensur[ing] that appropriate mechanisms and means are available (Article 33)."48 The Convention maintains a focus on consultation and participation, with a view to stimulating dialogue between governments and indigenous and tribal peoples and has been used as a tool for development processes, as well as conflict prevention and resolution.

Article 33 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Art. 33) indicates that "States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources".

Domestic law

In certain jurisdictions, there is well established, highly articulated legislation in place prohibiting the violation of indigenous peoples' rights, as well as effective enforcement. In these countries, the legal risks associated with complicity in human rights violations are likely to be serious. On the other hand, jurisdictions with comprehensive legal regimes and a strong rule of law provide businesses with regulatory predictability and certainty, which plays an important role in risk mitigation as the standards attached to business conduct are clear.

In ‘weaker jurisdictions' characterised by variables such as legal loopholes, corruption and flawed judicial processes, the reputational risk related to the infringement of indigenous rights may outweigh the legal risks – due to poor regulatory enforcement.

Nonetheless, it is useful to examine legislation and legal precedents from a range of countries to identify the higher legal standards that MNCs should aspire to – and which will, over time, become more common in a wider range of jurisdictions as companies are held more accountable for their human rights impacts.

Free, Prior Informed Consent

One of the areas in which litigation is common in relation to indigenous rights is on the topic of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) obligations placed on government and, in some cases, businesses.

The following is a selection of FPIC requirements from a range of different countries in which businesses may be required to engage with indigenous communities:

- In Australia, Canada, the US, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Peru, in order to purchase land from traditional owners, industry representatives must establish a mutual agreement with the landowners

- In the Philippines, according to the Mining Act (1995) and Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (1997) ‘prior informed consent' is required at least at the exploration stage. This same obligation is found in Australia – with the first piece of state legislation to introduce this requirement being the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act (1976).

- In Canada, where land titles have been solidified, (for instance, on reserves, as well as in Nunavut), consent is required. On land where land settlements have yet to be finalised, there is a ‘right to consult' which is verified by officials dealing with the permitting process

- In the US, on Native American reservations and trust lands, tribes often have not only surface rights but also mineral rights, and in this context, tribal council approval is required

Land claims

In many countries there are ongoing land claim disputes between governments and indigenous peoples, which has the effect of putting property rights in certain territories ‘in limbo'. However, landmark rulings in the following countries have determined the legal requirements attached to land claims in definitive terms:

- The Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997) defined the nature of aboriginal title as a collective-proprietary right. In doing so, the court established a distinction between the proprietary rights to which all Canadian citizens are entitled and aboriginal title. The ruling indicated that aboriginal title "is not a mere private property right, but a communal right that includes governmental authority and therefore is more in the nature of title to territory than title to land"

- Courts in Australia have recognised the customary and traditional property rights of indigenous peoples through Mabo v. Queensland (1992), a High Court case. The ruling dictates that native land titles are both communal in nature and emerge from traditional laws of indigenous tribes

- The US Supreme Court in its decision in Lyng v. Northeast Indian Cemetery Protective Association (1988) accepted the connection between tribal cultural survival and legal protection of the natural environment

Litigation risks

The legal risks emanating from litigation with indigenous groups can be very costly for business. There are numerous examples of multinational businesses engaged in lengthy legal battles over allegations of human rights abuses and environmental degradation.49

Ecuador: One of the most high profile cases involves the operations in Ecuador of Texaco Petroleum, a subsidiary of Chevron. Ecuadorean Amerindian groups filed lawsuits in US courts in the early 1990s, alleging that Texaco, which was acquired by Chevron in 2001, polluted the jungle and damaged their health by dumping 68bn litres of contaminated water into the jungle over a period of 20 years (between 1972 and 1992). Chevron acknowledges that there has been pollution in the Amazon but denies that it is legally responsible for the clean-up.50

In June 2009, Chevron said it had exhausted attempts to reach a settlement with the plaintiffs. Lawyers for the company also alleged that the trial was influenced by Ecuadorean politics. The verdict handed down by Ecuadorean courts in August 2012 resulted in damages that amount (following appeals) to around US$19bn. In 2013, the Supreme Court upheld the August 2012 verdict for environmental damages, but halved the damages to $9.51 billion. Chevron refused to pay on the basis that the ruling was illegitimate and accused lawyers and supporters of indigenous groups who brought the case of "corrupting the trial".51 In March 2014, a US court ruled that the Ecuadorian ruling could not be enforced as it was fraudulent.

Chevron has no in-country assets, meaning the plaintiffs are seeking to enforce the judgement against their subsidiaries in Argentina, Brazil and Canada. For example, in September 2015, Canada's Supreme Court ruled that Ecuadorian villagers can pursue their case against Chevron in Canada.

Notwithstanding the ultimate outcome of the litigation, the case has generated a significant amount of reputational risk – due to widespread criticism by a range of shareholders of the company's actions in Ecuador.

Kenya: The Endorois case (CEMIRIDE v. Kenya) at the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights is one of the most recent and prominent examples of the legal risks that businesses could potentially face on the topic of indigenous rights. A ruby mining concession was granted to a multinational company on Endorois ancestral land. The May 2010 judgment suggested that the Endorois should have their land restored, titled and demarcated. In addition, the Commission found that the eviction, with minimal compensation, violated the Endorois' right as an indigenous people to property, health, culture, religion, and natural resources.52 In June 2014, the World Heritage Committee designated the lands around Lake Bogoria as a World Heritage Site, requiring the Kenyan government to obtain the full and effective participation of the Endorois in the management of the area through their own representative institutions. Canada: In June 2014, the Canadian Supreme Court formally declared that a specified area within British Colombia holds Aboriginal title, belonging to the Tsilhqot'in nation. Although the ruling did not make significant changes to laws concerning Aboriginal land titles, the court confirmed that indigenous titles can exist over broad areas of land that were subject to occupation at the time sovereignty was asserted. This landmark ruling has paved the way for a number of actions taken by indigenous communities, including eviction notices being issued to a railway company and a public park, as well as a lawsuit launched against the Enbridge tar sands pipeline. In addition, the Atikamekw First Nation declared sovereignty over 80,000 square kilometres of territory in Quebec, stating that any development in the area must occur in cooperation.53

It is noteworthy that ‘public interest litigation' has become a popular vehicle for groups (including indigenous groups) in many developing countries such as India and the Philippines, to access environmental justice. In jurisdictions that take a liberal approach towards 'legal standing', NGOs have been able to make successful interventions on behalf of individuals and groups, helping to vindicate their claims.54

Operational risks

The tactic of blocking roads and disrupting the transporting of products and supplies has been used on numerous occasions by disgruntled indigenous groups. In October 2015, for example, indigenous communities from around the world gathered on the banks of the Baram River in Sarawak, Malaysia to celebrate the second anniversary of the indigenous-led blockades against the proposed dam being built by Sarawak Energy on the Baram River. The blockades prevented workers and researchers from accessing the site, causing works at the dam to come to a standstill. In September 2015, the local government of Sarawak announced a moratorium on the proposed project.55

In areas that are heavily militarised, the tension created by blockades can escalate rapidly and result in violent encounters. This occurred in Panama in 2012, when the government ordered armed police to end a week-long blockade of nine highways, including the Interamerican Highway that links Panama with Costa Rica. The armed forces were reported to have used violent force against protestors, resulting in the death of one indigenous man and injuries to 32 protestors and 7 police officers.56

Financing risks

As noted above, international financing organisations have integrated the need to respect indigenous rights into their lending conditions. For example

The IFC has integrated the requirement for the Free, Prior and Informed Consent of indigenous communities into its latest 2012 Performance Standards. Performance Standard 7: Indigenous Peoples requires FPIC for those projects that impacts on indigenous land or resources, requires the relocation of indigenous peoples or impacts on "critical cultural heritage."57

The World Bank's Operational Manual 4.10 (2005) requires broad, well-informed support for projects from relevant indigenous communities, as well as informed participation at each stage and throughout the life of a project. In addition, the World Bank Safeguard on Environmental Assessment requires that the project proponent "consults project-affected groups and local non-governmental organisations about the project's environmental aspects"

- The Inter-American Developmental Bank (IDB) Strategies and Procedures on Socio-Cultural Issues as Related to the Environment mandate that the IDB will not support projects affecting tribal lands and territories "unless the tribal society is in agreement."58

In this context, if companies or their business partners are found to be falling short of applicable criteria, they face potential penalties, restrictions on their ability to raise finance and the inability to provide mainstream investors with assurance around projects in high-risk areas. (For example, this may include the absence of IFC participation in the overall financing portfolio).

Reputational risks

If a company is perceived to abuse the rights of indigenous communities, it may end up alienating a range of stakeholders including consumers, investors, current employees, prospective employees and civil society members.

This has the potential to result, for example, in:

- Reduced sales as a result of brand erosion amongst consumers who are either part of, or sympathetic to, indigenous groups that are perceived to be subject to discriminatory practices

- Divestment by ethical investment organisations who perceive a discriminatory approach to indigenous rights

There is a large range of groups campaigning on behalf of indigenous communities that seek maximum exposure for their concerns. The Declaration of Lima, promulgated in 2010, is just one example of the networks of civil society groups rallying for the cause of indigenous peoples on topics such as climate change and issues surrounding the extractives sector. Evidently, the signatories of this Declaration will seek to cause legal and/or reputational damage to businesses they perceive to be operating in an irresponsible manner.

47 Asia Development Bank (ADB), 2009, Land and Cultural Survival: The Communal Land Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Asia, http://www.adb.org/Documents/Books/Land-Cultural-Survival/land-cultural-survival.pdf . See also Indigenous People Rights Monitor, 2008, Submission for Philippines Universal Periodic Review at the UN Human Rights Council, http://lib.ohchr.org/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/Session1/PH/IPRM_PHL_UPR_S1_2008_IndigenousPeopleRightsMonitor_uprsubmission.pdf .

48 ILO, 1989, Convention 169 on Tribal and Indigenous Peoples, http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C169. .

49 For instance, see the Barrick Gold lawsuit (re Western Shoshone tribes, USA) ; the BHP lawsuit (re Papua New Guinea) [Accessed on 2 August 2013];and the Cambior lawsuit (re Guyana)..

50 See: Chevron Corporation, ‘Texaco Petroleum, Ecuador and the Lawsuit against Chevron', http://www.chevron.com/documents/pdf/texacopetroleumecuadorlawsuit.pdf.

51 BBC News, March 2011, Chevron appeals against Ecuador Amazon pollution fine, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-12725490. [Accessed on 2 August 2013]. See also: Chevron Corporation, ‘Texaco Petroleum, Ecuador and the Lawsuit against Chevron', Ibid.

52 Human Rights Watch, February 2010, Kenya: Landmark Ruling on Indigenous Rights, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/02/04/kenya-landmark-ruling-indigenous-land-rights.

53 CBC News, 2014, ‘Atikamekw First Nation declares sovereignty over its territory,' Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/aboriginal/atikamekw-first-nation-declares-sovereignty-over-its-territory-1.2761105

54 Asia Development Bank (ADB), 2009 Land and Cultural Survival: The Communal Land Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Asia, http://www.adb.org/Documents/Books/Land-Cultural-Survival/land-cultural-survival.pdf.

55 Intercontinentalcry.org, 2015, ‘International Indigenous Anti-Dam Activists Join Two Year Anniversary Celebration of Blockades in Malaysia,' Available at: https://intercontinentalcry.org/international-indigenous-anti-dam-activists-join-two-year-anniversary-celebration-of-blockades-in-malaysia/

56 Latin American Bureau, 2012, Panama: violent repression of indigenous protests. Available at: http://lab.org.uk/panama-violent-repression-of-indigenous-protests

57 IFC, January 2012, Performance Standard 7: Indigenous Peoples, http://www1.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/1ee7038049a79139b845faa8c6a8312a/PS7_English_2012.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

Suggestions for responsible business

According to the UN ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy' policy framework59 as updated and elaborated last year in the Guiding Principles for the Implementation of the UN ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy' Framework60 businesses have a responsibility to respect all human rights. This responsibility requires businesses to refrain from violating the rights of others and to address any adverse human rights impacts of their operations.

To meet this responsibility to respect human rights, the framework notes that a responsible company should engage in human rights due diligence61 to a level commensurate with the risk of infringements posed by the country context in which a company operates, its own business activities and the relationships associated with those activities.62

The framework, as clarified by the Guiding Principles, specifies the main components of human rights due diligence:

- A policy statement articulating the company's commitment to respect human rights and providing guidance as to the specific actions to be taken to give this commitment meaning: This policy should be informed by appropriate internal and external expertise and identify what the company expects of its personnel and business partners. The policy should be approved at the most senior level and communicated internally and externally to all personnel, business partners and relevant stakeholders. In addition, it should be reflected in appropriate operational policies and procedures

- Periodic assessment of actual and potential human rights impacts of company activities and relationships: Human rights due diligence will vary in scope and complexity according to the size of a company, the severity of its human rights risks and the context of its operations. Impact assessment must be continuous, recognising that human rights risks may change over time as companies' operations and operating contexts evolve. The process should draw on internal and external human rights experts and resources. Furthermore, it should involve meaningful engagement with potentially affected individuals and groups, as well as other relevant stakeholders

- Integration of these commitments into internal control and oversight systems: Effective integration requires the responsibility for addressing the impacts by assigning it to the appropriate structures of the company. It also requires appropriate internal decision-making mechanisms, budget allocation and oversight processes

- Tracking of performance: Tracking of performance should be based on appropriate qualitative and quantitative metrics and should draw on feedback from both internal and external stakeholders. In addition, it should inform and support continuous improvement

- Public and regular reporting on performance: When reporting, companies should take into account the risks the communication of certain information may pose to stakeholders themselves, or to company personnel. In addition, the content of the reports should be subject to the legitimate requirements of commercial confidentiality

- Remediation: Where business enterprises identify responsibility for adverse impacts, they should cooperate will all relevant stakeholders in their remediation through legitimate processes.

The Guiding Principles emphasize the challenges of doing business in conflict-affected areas, by stating that ‘the risk of gross human rights abuses is heightened in [such areas]'.63 Businesses are advised to pay special attention to both gender-based and sexual violence which tend to be especially prevalent during times of conflict.64 The Commentary to this section of the Guiding Principles states that ‘[i]nnovative and practical approaches are needed' in order to avoid contributing to human rights violations in these environments.

While designing its Human Rights Impact Assessment, businesses may wish to consult existing guidance documents, such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), UN Global Compact and International Business Leaders Forum's (IBLF) Guide to Human Rights Impact Assessment and Management.65 This latter guide provides companies with a ‘process to assess their business risks, enhance their due diligence procedures and effectively manage their human rights challenges.' The online guide takes users through different stages of the impact assessment process, including Preparation, Identification, Engagement, Assessment, Mitigation, Management and Evaluation.

Specific actions that responsible business might take include:66

1. Impact assessment and the determination of engagement partners

Companies should undertake an assessment of their actual and potential impacts on the rights of indigenous people, focused on (within the specific context of their operating environment):

- Their own business activities

- Their relationships with third-parties – including business partners

This impact assessment can take a variety of forms depending on the size of the company, the nature of the context and other relevant variables. As a result, it can range from a high-level desk-based assessment to a much more in-depth exercise based on on-the-ground reconnaissance, direct consultation of indigenous communities, a search of government documents (including, for example, land registry records), engagement with local civil society stakeholders and, if relevant, other businesses operating in the area.

This step is a vital precursor to embarking on any sort of presence in a new location, even if there is an absence of strict free, prior, informed consent regulations embedded within the jurisdiction. In addition, meeting with local communities, both indigenous and non-indigenous, before commencing operations will help cultivate good faith and start the engagement in a positive manner. This initial contact is vital if the ultimate goal is to develop a positive, mutually beneficial relationship that can be the foundation for effective sustainable development activities moving forward.